When he first began documenting the adobe churches and moradas — some dating back to the 17th century — that were subject matter for his best known artworks, several of the structures were in a state of collapse.

Waldrum founded the El Valle Foundation (named for “la iglesia de San Miguel” in El Valle New Mexico) to raise consciousness of, and funds for, the most endangered structures.

The video below was made by Heese/Waldrum Studios to be shown at fund raisers for the endangered historical buildings. Despite the efforts of Waldrum and the El Valle Foundation, la iglesia de San Miguel was razed in September of 1985.

Restoration of Spirit: Harold Joe Waldrum Envisions a Bright Future for the Old Adobe Churches of New Mexico

Article by Greg Firlotte for Designs West Magazine, 1982. Photography by Steve Bradley and Warren Hanford.

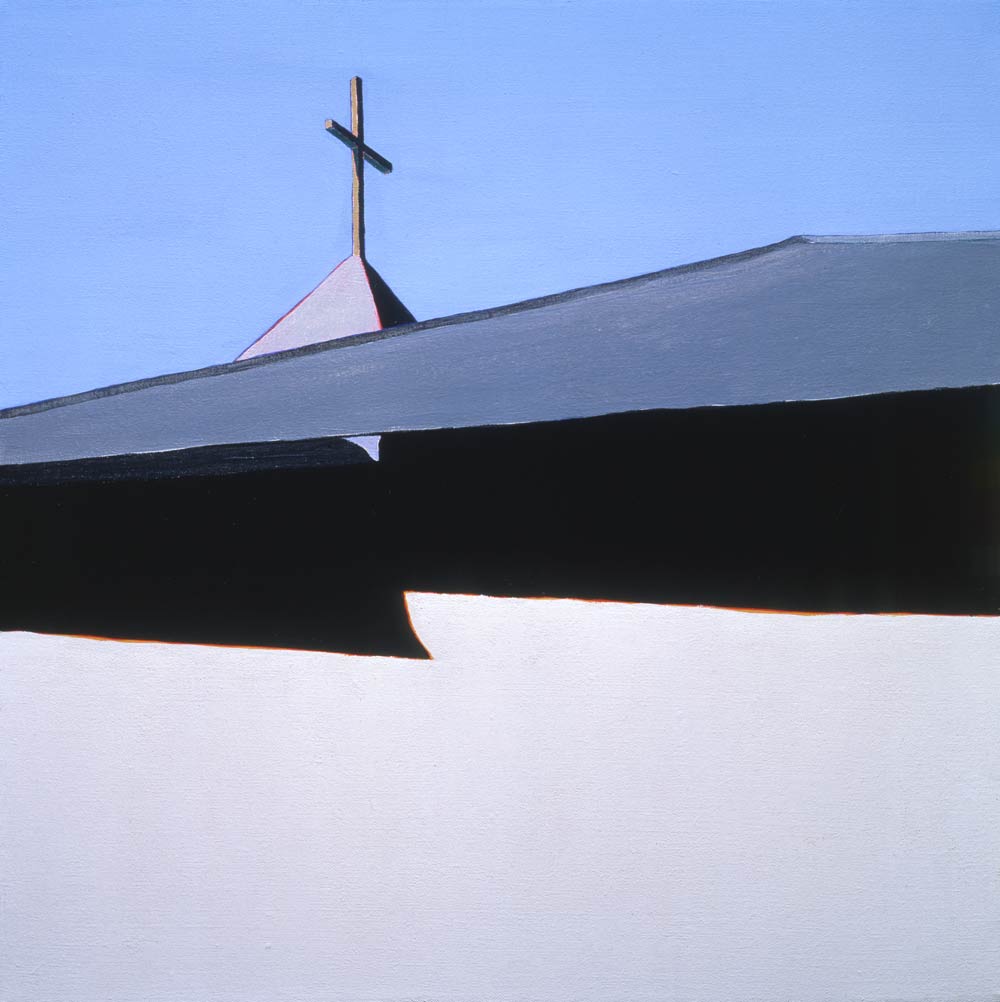

What started out as a challenge of sorts has turned into a very engaging endeavor for artist Harold Joe Waldrum. It was several years ago after a showing of his paintings in Santa Fe, New Mexico that an art critic commented on Waldrum's Window Series paintings. The critic thought the style to be more East Coast-like than Southwestern in its relevance. Thinking upon this criticism while driving from Santa Fe to his home in Taos, Waldrum passed the well-known St. Francis of Assisi church in Ranchos de Taos. As a joke, he thought that he should paint it for his token "Southwestern Painting."

“I thought that this first painting, Ranchos, was okay,” recalls Waldrum, “considering that it was somewhat outside the style I had been working in at the time.”

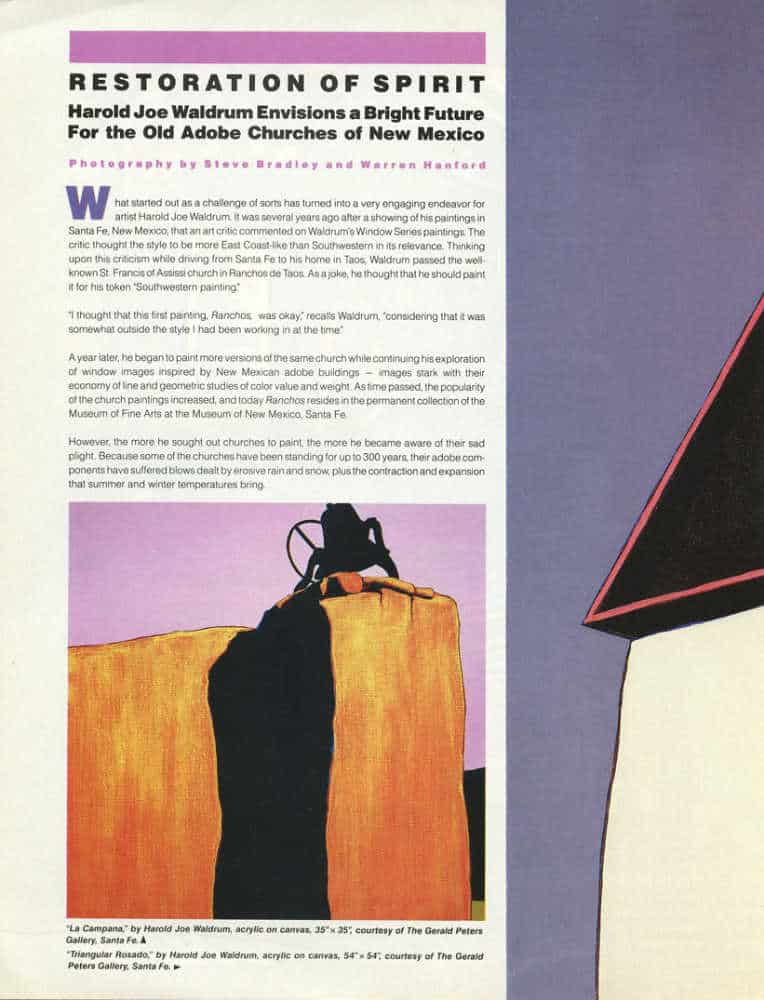

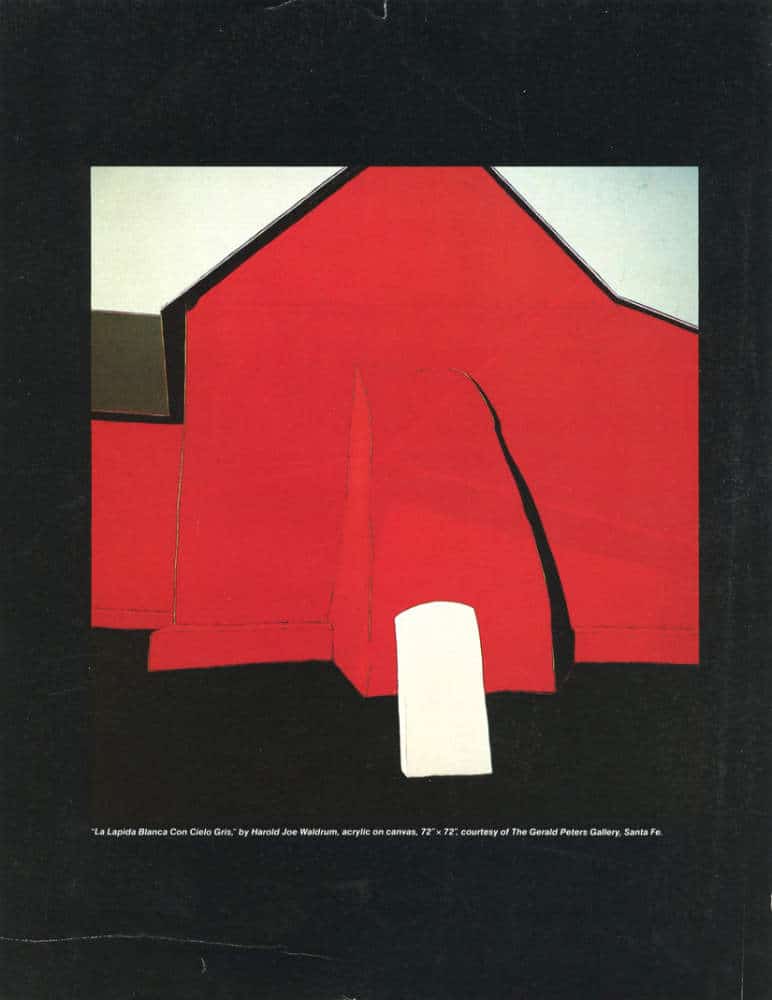

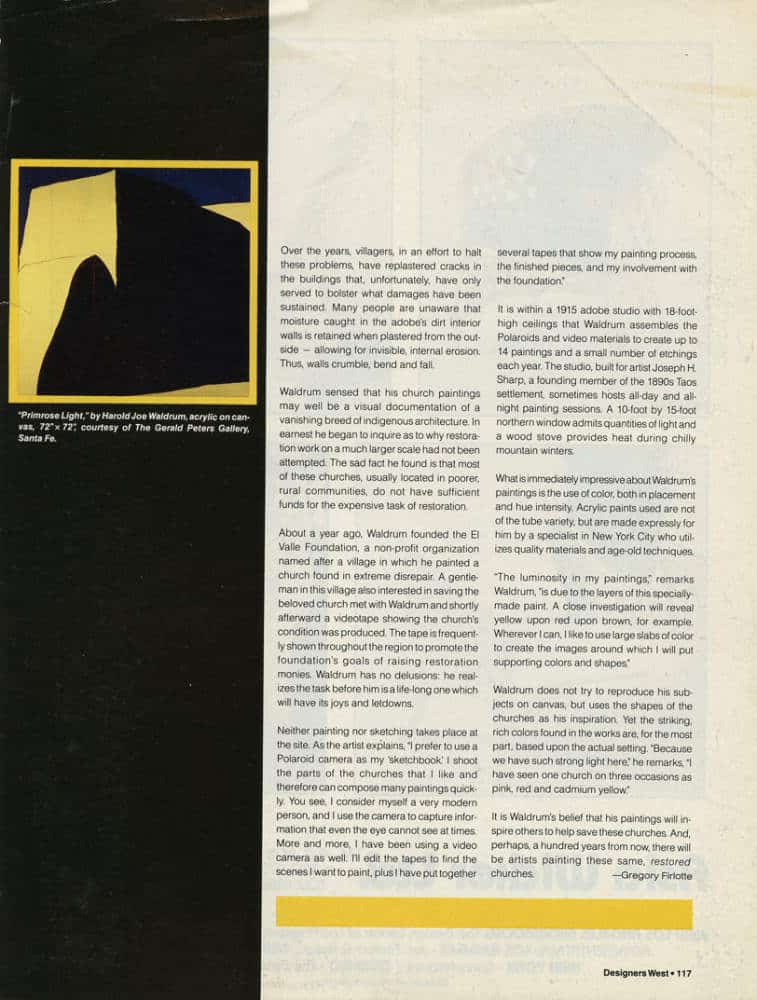

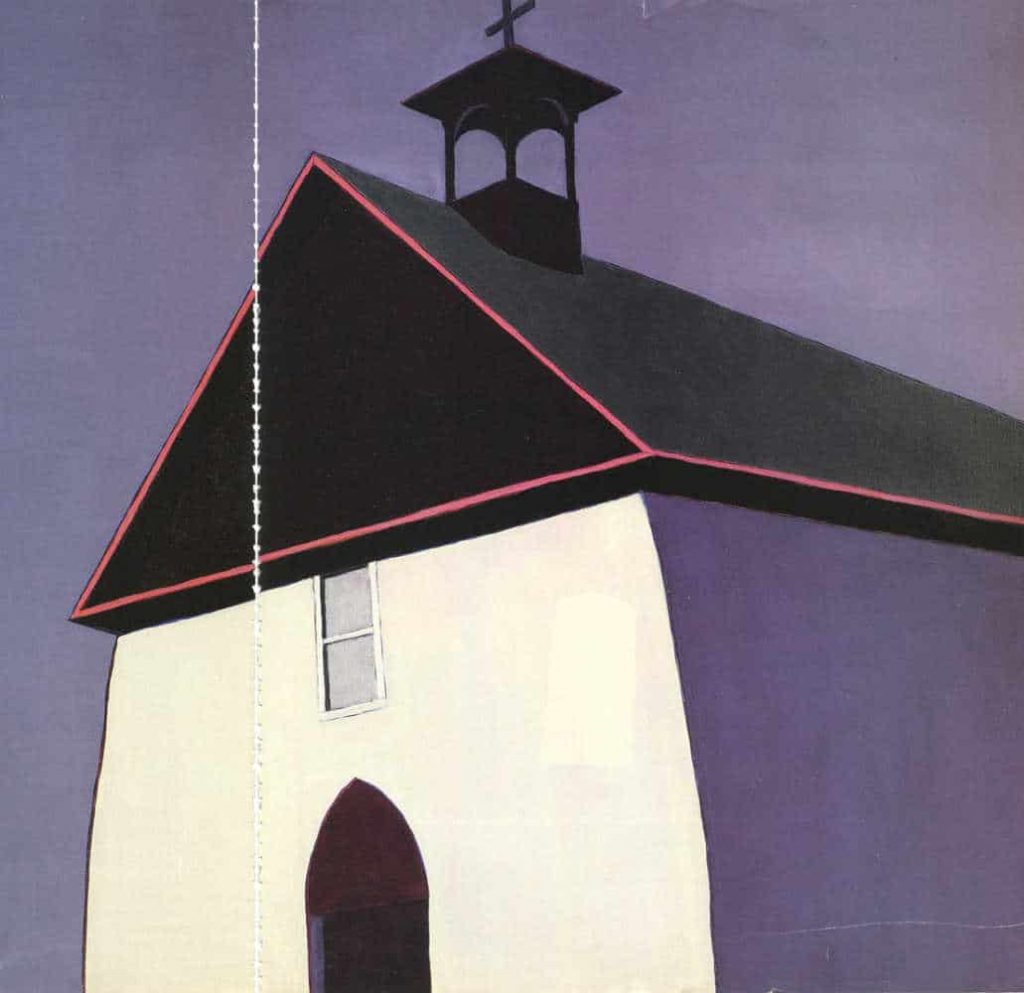

A year later, he began to paint more versions of the same church while continuing his exploration of window images inspired by New Mexican adobe buildings — images stark with their economy of line and geometric studies of color value and weight.

However, the more he sought out churches to paint, the more he became aware of their sad plight. Because some of the churches have been standing for up to 300 years, their adobe components have suffered blows dealt by erosive rain and snow, plus the contraction and expansion that summer and winter temperatures bring.

Over the years, villagers, in an effort to halt these problems, have replastered cracks in the buildings that, unfortunately, have only served to bolster what damages have been sustained. Many people are unaware that moisture caught in the adobe's dirt interior walls is retained when plastered from the outside — allowing for invisible, internal erosion. Thus, walls crumble, bend and fail.

Waldrum sensed that his church paintings may well be a visual documentation of a vanishing breed of indigenous architecture. In earnest he began to inquire as to why restoration work on a much larger scale had not been attempted. The sad fact he found is that most of these churches, usually located in poorer, rural communities, do not have sufficient funds for the expensive task of restoration.

About a year ago, Waldrum founded the El Valle Foundation, a non-profit organization named after a village in which he painted a church found in extreme disrepair. A gentleman in this village also interested in saving the beloved church met with Waldrum and shortly afterward a videotape showing the church's condition was produced. The tape is frequently shown throughout the region to promote the foundation's goals of raising restoration monies. Waldrum has no delusions; he realizes the task before him is a life-long one which will have its joys and letdowns.

Neither painting nor sketching take place at the site. As the artist explains, “I prefer to use a Polaroid camera as my ‘sketchbook.’ I shoot the parts of the churches that I like and therefore can compose many paintings quickly. You see, I consider myself a very modern person, and I use the camera to capture information that even the eye cannot see at times. More and more, I have been using a video camera as well. I'll edit the tapes to find the scenes I want to paint, plus I have put together several tapes that show my painting process, the finished pieces, and my involvement with the foundation.”

It is within a 1915 adobe studio with 18-foot ceilings that Waldrum assembles the Polaroids and video materials to create up to 14 paintings and a small number of etchings each year. The studio, built for artist Joseph H. Sharp, a founding member of the 1890s Taos settlement, sometimes hosts all-day and all-night painting sessions. A 10-foot by 15-foot northern window admits quantities of light and a wood stove provides heat during chilly mountain winters.

What is immediately impressive about Waldrum’s paintings is the use of color, both in placement and hue intensity. Acrylic paints used are not of the tube variety, but are made expressly for him by a specialist in New York City who utilizes quality materials and age-old techniques.

“The luminosity in my paintings,” remarks Waldrum, “is due to the layers of this specially-made paint. A close investigation will reveal yellow upon red upon brown, for example. Wherever I can, I like to use large slabs of color to create the images around which I put supporting colors and shapes.”

Waldrum does not try to reproduce his subjects on canvas, but uses the shapes of the churches as his inspiration. Yet the striking, rich colors found in the works are, for the most part, based on the actual setting. “Because we have such strong light here,” he remarks, “I have seen one church on three occasions as pink, red and cadmium yellow.”

It is Waldrum's belief that his paintings will inspire others to help save these churches. And, perhaps, a hundred years from now, there will be artists painting these same, restored churches.

—Greg Firlotte